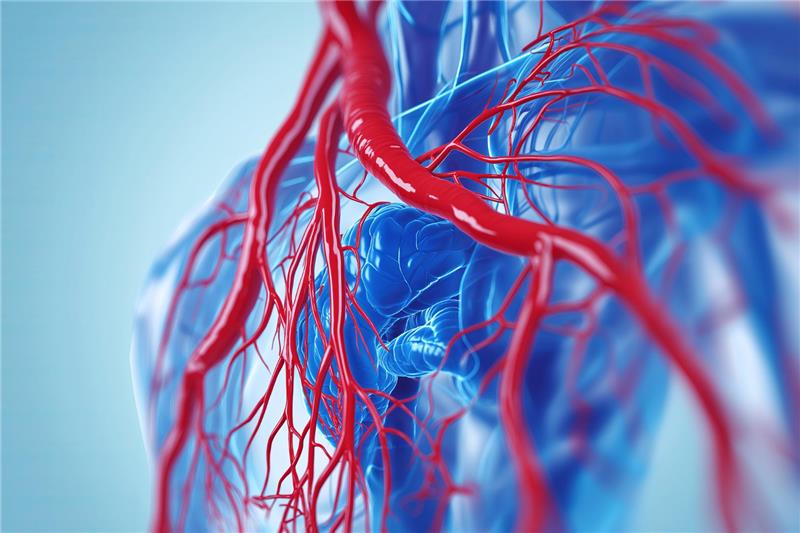

Heart failure is a complex cardiac condition where the heart cannot pump blood effectively to meet the body’s needs. It’s not a singular disease but a clinical syndrome that can result from various heart impairments. Based on the chamber affected and the resulting physiological changes, heart failure is broadly classified into left-sided, right-sided, and congestive heart failure. Knowing these distinctions helps guide proper diagnosis, therapy, and monitoring.

Left-Sided Heart Failure: The Primary Culprit

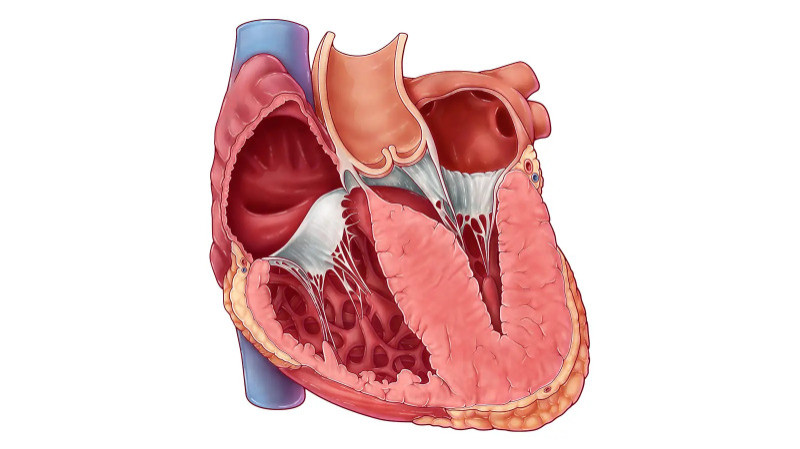

Left-sided heart failure is the most commonly diagnosed form. It originates in the left ventricle—the main pumping chamber that delivers oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. When the left ventricle loses its strength or becomes too stiff, blood flow slows and backs up into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion.

This condition manifests as two subtypes: systolic failure, where the heart muscle becomes too weak to contract forcefully, and diastolic failure, where the chamber becomes rigid and cannot fill adequately. Individuals often experience shortness of breath, fatigue, chest discomfort, and a persistent cough, especially when lying flat. Over time, the reduced cardiac output may lead to impaired kidney function and systemic complications.

Right-Sided Heart Failure: The Backflow Effect

Right-sided heart failure affects the heart’s right ventricle, which is responsible for sending deoxygenated blood to the lungs for oxygenation. When this chamber weakens, it causes a backup of blood in the body’s veins. This results in visible swelling, particularly in the lower limbs, ankles, and abdomen.

Though it can arise independently—often due to chronic lung diseases like COPD or pulmonary hypertension—right-sided failure is more frequently a downstream effect of long-standing left-sided failure. Signs include puffy legs, abdominal bloating, sudden weight gain, and fullness due to liver or gastrointestinal fluid accumulation.

Congestive Heart Failure: A Clinical End Stage Congestive heart failure (CHF) is not a separate form but rather a severe stage where both sides of the heart are affected. The term "congestive" refers to fluid buildup in tissues and organs stemming from poor circulation. CHF is typically characterized by widespread swelling, breathlessness, and fluid retention in the lungs, legs, and abdomen.

Symptoms worsen at night, and people often wake up breathless or need extra pillows to sleep comfortably. If not promptly managed, CHF can lead to repeated hospitalizations, organ dysfunction, and diminished quality of life.

Causes and Risk Factors Several underlying conditions can lead to heart failure. Coronary artery disease, previous heart attacks, hypertension, and damaged heart valves are major causes. Other risk factors include diabetes, thyroid disorders, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, viral infections, and genetic cardiomyopathies. Younger patients may develop heart failure due to inherited conditions that weaken the heart muscle over time.

Diagnosing the Type of Heart Failure

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment. Physicians rely on a combination of imaging tests and blood work. An echocardiogram assesses heart muscle contraction and identifies structural abnormalities. Chest X-rays reveal lung congestion, while BNP blood tests indicate fluid overload. ECGs evaluate heart rhythm, which may be disrupted in advanced stages.

Differentiating between left-sided, right-sided, and congestive forms ensures patients receive tailored therapies and early intervention.

Treatment Approaches and Evolving Medications

Heart failure management revolves around improving cardiac function, relieving symptoms, and preventing hospital admissions. Traditional therapies include ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and diuretics to reduce fluid retention and blood pressure.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) such as spironolactone or eplerenone have become essential, particularly for individuals with reduced ejection fraction, as they curb hormonal damage and enhance survival.

For patients not responding to standard medications, newer therapies like Vericiguat provide hope. This oral drug enhances nitric oxide signaling to improve vascular tone and has shown promise in late-stage heart failure.

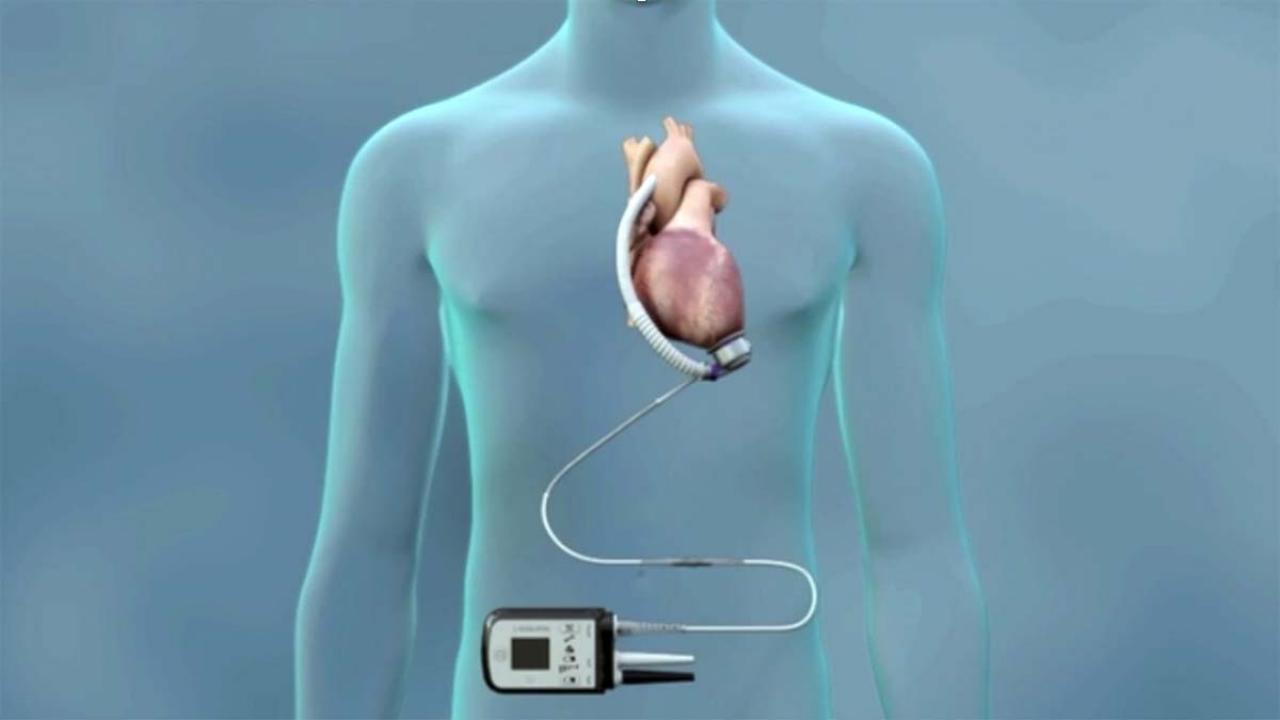

Role of Cardiac Devices and Emerging Technologies

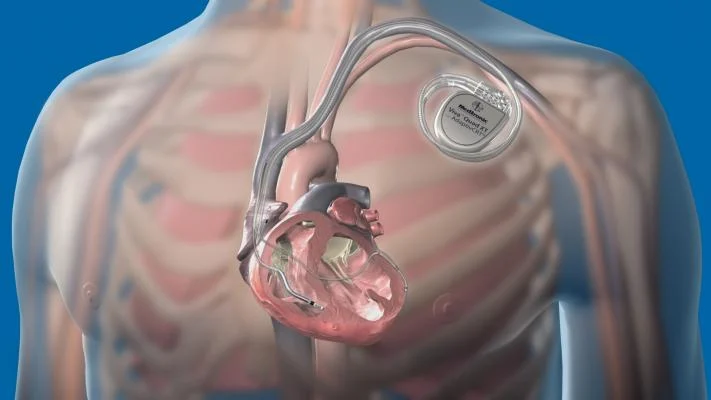

In cases of progressive heart failure, medications may be supplemented with device-based therapies. Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs) prevent sudden cardiac death by correcting arrhythmias, while Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) devices (CRT-P for pacing and CRT-D with defibrillator) help synchronize heartbeats in patients with conduction delays.

Cardiac Contractility Modulation (CCM) devices are another breakthrough for patients with moderately reduced heart function. These wearables deliver non-excitatory electrical pulses during the absolute refractory period, enhancing contractile strength without altering rhythm.

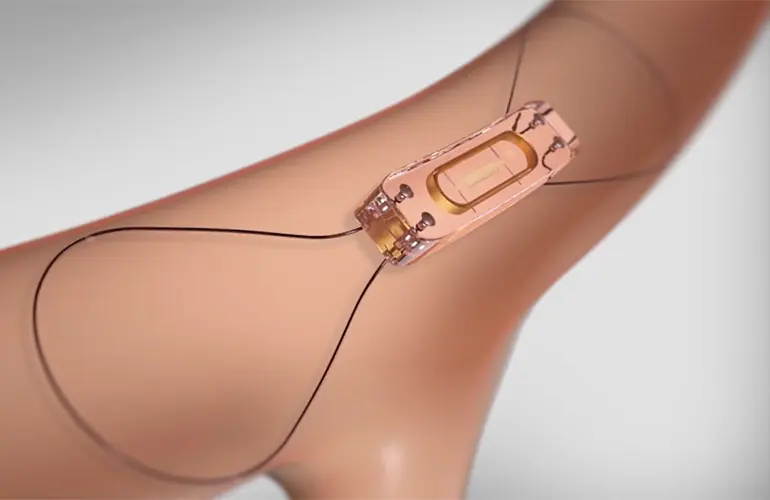

Pressure sensor loops have also revolutionized monitoring. These implantable sensors measure pulmonary artery pressures in real-time and transmit data wirelessly, allowing physicians to detect fluid retention before symptoms emerge. Early detection reduces hospitalizations and improves patient outcomes.

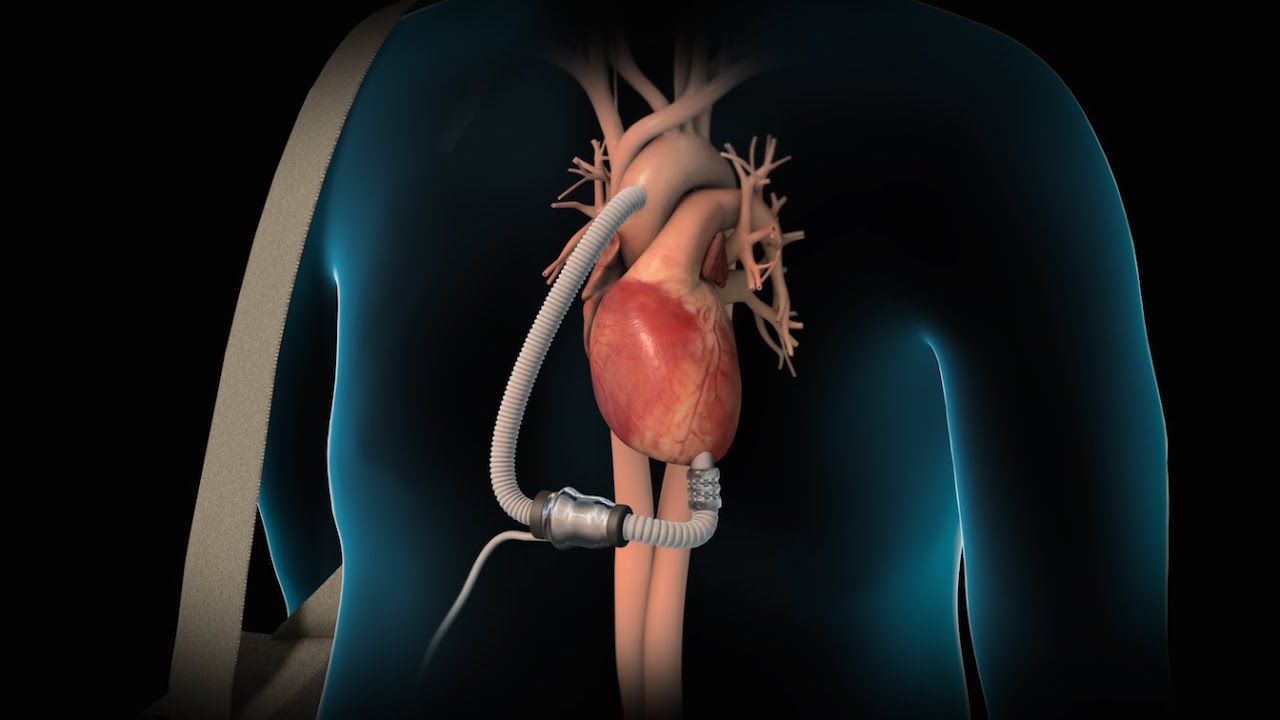

RVADs: Mechanical Support for Failing Right Hearts

For patients with severe right-sided heart failure who don’t respond to medication, Right Ventricular Assist Devices (RVADs) provide mechanical support. These devices pump blood from the right ventricle to the lungs, ensuring adequate oxygen exchange. RVADs are used as a bridge to transplant or in temporary support following heart surgery or severe pulmonary failure.

Though more commonly used in advanced settings, RVADs are lifesaving for select patients with isolated right ventricular dysfunction, especially when medical management fails.

Conclusion

Heart failure is a dynamic and multifactorial condition that may affect the left, right, or both sides of the heart. While left-sided failure leads to pulmonary congestion, right-sided failure causes systemic fluid buildup. Congestive heart failure represents the culmination of these processes, often requiring intensive treatment.

Modern advances such as MRAs, Vericiguat, CRT devices, ICDs, CCM therapy, RVADs, and pressure sensor monitoring have reshaped how clinicians manage and monitor this condition. Personalized therapy, regular follow-up, and the integration of cutting-edge technologies offer hope to many individuals living with heart failure, enabling them to lead longer, more active lives.